Inventory and cost of goods sold are probably the most complex accounting concepts that makers and crafters have to tackle. Today I’m going to attempt an overview of some important inventory concepts in simple, plain English. In part 2, I’ll delve into dealing with cost of goods sold (COGS).

Whether or not to keep detailed inventory counts & records can be a somewhat controversial topic in the maker community. There’s a lot of debate out there about whether the IRS requires small biz makers & crafters to track inventory and COGS or not.

Before I dive in, understand that accurately recording your inventory and supply costs is important for both taxes and bookkeeping purposes. It can save you a big headache in case of an audit, but it can also help you accurately price your goods and ensure profitability for your shop.

Does inventory even apply to me?

If you sell physical goods, then you likely have to deal with inventory. This true whether you’re crafting items from supplies (like a jewelry maker), making goods to order, buying finished goods at wholesale and simply reselling them, sourcing vintage goods and selling them at a markup, or anything in between.

You do not have to deal with inventory if you’re strictly a service provider, or if you sell only digital goods (lucky, lucky you!).

What is considered inventory?

For tax purposes, all of the following are considered to be inventory:

finished goods –

In general, your inventory includes the finished products you have for sale on your shelf.

What does that mean? If you’re a maker or a crafter, and you make items and then list them for sale or bring them to a craft show, all those items you have up for sale are considered your inventory. They’re really considered inventory whether you’ve already got them listed for sale, or whether they’re in a pile waiting to be stocked. If it’s a finished item ready to go, then it’s part of your inventory.

works in progress –

If there’s stuff you’re working on that’s not “finished” but a work-in-progress, that’s considered part of your inventory too.

inventoriable raw materials & supplies –

To make matters more complex, some of your materials and supplies are considered part of your inventory as well. We’ll discuss that in the next question.

The important thing to note here is that for tax purposes at least, inventory is not just your finished goods. Inventory has to include your giant supply stash as well. Please note that “inventoriable supplies” is a term that I’ve made up myself, just to easily distinguish supplies that are supposed to be part of inventory vs. supplies that don’t have to be part of your inventory, which leads me to…

What raw materials & supplies are considered “inventoriable”?

Your materials & supplies probably make up the biggest spending category for your handmade biz. So, it’s really important to know – what materials & supplies are considered “inventoriable” and need to be part of your inventory?

Any raw materials or supplies that go directly into your finished goods are considered inventoriable for tax purposes. So if you make purses, your inventoriable supplies would include fabric, zippers, or buckles. If you make jewelry, your inventoriable supplies would include beads and earring studs. If you create felt banners, your inventoriable supplies would include felt and twine. Basically all those supplies that you hoard from Hobby Lobby fall into the inventory bucket, as long as you’re using them in the goodies you sell.

What raw materials & supplies are not part of inventory?

Materials & supplies that are purchased for general business use that do not go directly into the items you sell are not part of inventory. These are things like office supplies (printer ink and printer paper), tools (scissors, pliers, or paint brushes), packaging supplies, etc. You may use your tools to make your goods, but they are not part of your goods, thus they don’t have to be included in inventory.

Materials & supplies that are considered “incidental” are also not part of your inventory, even if they go into your finished goods. Incidental materials are supplies that are difficult to measure or trace, or they are just a tiny unimportant piece of your good. Examples are supplies like thread or glue. You might use these in the products you sell, but knowing exactly how much thread you have on hand would be pretty darn hard to measure, plus the cost of the incidental supply used throughout the year is probably pretty minimal.

Note that, for tax purposes, all of these non-inventoriable supplies can be expensed (or deducted) in the year you purchase them. This is an important distinction that I will explain in detail later. Just remember – non-inventoriable supplies can be deducted in the year of purchase. Inventoriable supplies can only be deducted (as part of COGS) in the year you sell the item made with that supply.

When determining whether a supply is incidental or not, keep in mind that our goal is always to give an accurate and clear picture of our business’ net income. If you have paint as a supply, that is indeed something that’s hard to trace or measure. But if paint is a big piece of what you sell (like painted wooden signs for example), and you spend quite a bit on paint and have a lot of paint sitting around at any point in time, chances are your paint is not an incidental expense or supply and you should be inventorying it.

OK, so how do I record and track my inventoriable supplies?

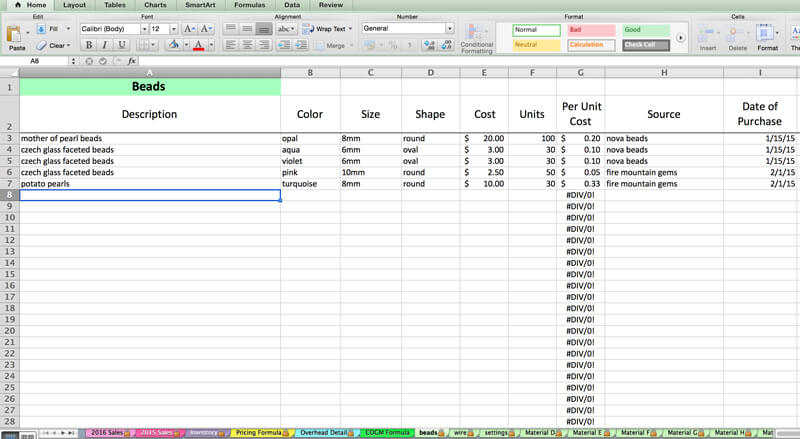

As you purchase inventoriable raw materials and supplies, you should have a system of entering the necessary information for each item. {I highly recommend a Paper + Spark inventory spreadsheet for keeping track of these items. This spreadsheet does a lot of the math work for you, and helps you keep track of supplies, inventory totals, and COGS on an on-going basis.}

You will need to record the cost of each supply item and the quantity purchased. When I say the cost of the item – I mean the actual amount you paid, including any discounts, coupons, sales taxes, or shipping. (If you’re wondering how to divide shipping cost amongst multiple supply items purchased at once, check out my shipping guide here.)

When I say quantity purchased – I mean in whatever unit of measurement that makes the most sense to you. That could be an actual count, square inches, square feet, weight in ounces, etc. Chose a unit of measurement for each type of supply and be consistent with each purchase.

You should then determine your newly purchased supply’s cost per unit. Cost per unit is simply the cost of your supplies divided by the quantity purchased. You can do this manually on a calculator, or use a system that will take your two inputs and automatically calculate the cost per unit for you, like our Inventory for Handmade Sellers spreadsheet.

Why does cost per unit matter?

In order for you to know how much a finished good cost you to create, you need to know the cost per unit of all your supplies. So now when you make a new pair of earrings, you can say these earrings used X number of beads, and each bead cost me $X, and each earring hook cost me $Y. So now I’m able to calculate exactly how much this pair of earrings cost me to create in terms of supplies.

Knowing exactly how much in supplies goes into a finished product is not just important for tax purposes, it helps with pricing too. Read more about pricing accurately based on your costs here.

How do I value my inventory?

Inventory should be valued at cost, not at retail. That means for finished goods, you need to know how much that good cost you to create in terms of inventoriable supplies (which you can easily calculate if you’re keeping track of the cost per unit!). This way you can easily calculate the cost of every little bit that went into creating your item.

You are welcome to keep track of the retail value of the inventory you have on hand, but you do not need to know this for tax purposes (you might need to know it for insurance or bookkeeping purposes, though).

What is “cost of goods made”?

I like to call the total cost of all my finished goods the cost of goods made. It’s just another way of looking at the cost of all the finished goods waiting to be sold on your shelf. Once an item sells, it’s “cost of goods made” magically turns into it’s cost of goods sold (cause it sold, get it?).

Do I even have inventory?

If you create items to order, like someone who makes custom baby clothes, you probably still have inventory. This is because you still have supplies on hand, and remember, your inventoriable supplies are considered inventory. Just because you don’t keep finished goods on your shelf doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t have inventory (sorry!).

If you create products on demand and you don’t keep any supplies on hand, then you might truly have $0 of inventory. An example would be Paper + Spark, my own biz. I use a drop-shipper to fufill my orders, and do not create a mug or a journal until someone orders it. I truly do not keep any supplies or inventory on hand, since my business is made-to-order digitally designed products. However! I still do have cost of goods sold.The really important part – Why does any of this matter?

I’ve been telling you all about what inventory is and isn’t, but I haven’t really explained why it’s so important to be keeping track of it. Inventory matters for tax purposes. Here’s the bottom line – you cannot deduct the cost of your inventory until you sell it.

Let that sink in for a moment. What exactly does this mean?

You’re a business owner. You’re (hopefully) doing your tax return each year. Your biz spends money on all sorts of business expenses – printing, advertising costs, staples, beads, fabric, transaction fees, craft show booth rental, etc. At year-end, you are deducting most of these business expenses. Deductions are good. They are subtracted from your business income & sales so that you owe less in taxes. Yay! More deductions means less tax. For the most part, you can deduct these business expenses in the year you paid them.

But – you cannot deduct inventory OR those inventoriable supplies & materials until the year the item you created with that supply actually sells.

This is why you have to keep track of your inventory! Think about it. When I first started selling jewelry, I went buckwild buying beads, crystals, and sparkly things galore. I probably bought more supplies than I could make jewelry with in a decade. How nice would it be if I could just deduct the cost of all those shiny things on my tax return? If I had the money, I could just buy supplies all day and never have to pay a dime in taxes for my biz.

This isn’t how it works. Unfortunately, you can’t just go out and buy a bajillion dollars worth of beads and then deduct that in the year you bought them. You have to wait until the items you create with those beads actually sell, then you get the deduction.

When you buy the beads, they become part of your inventory amount (remember, valued at cost). Your inventory amount is essentially, for accounting purposes, considered an asset. It just sits on your “books” as an asset, until you sell the item. Then, it becomes a deduction in the form of cost of goods sold on your tax return.

Each year on your tax return you will fill out a little section on your inventory and cost of goods sold. We’ll cover this in part 2, along with exactly how that cost of goods sold deduction works and how to keep track of it.

BTW, inventory is perpetual.

That means it’s something you keep track of over time, across years. Unlike your regular ol’ expenses, you don’t just go back to zero on January 1. You will need to know your inventory amounts at year end, and then that amount rolls over to the next year, and you keep building or subtracting. You have to do it this way because in real life, you will be selling items that you created last year. Or you might be making items this year with supplies that you bought 3 years ago. Thus, inventory is perpetual.

Keep truckin’…

What questions do you still have about inventory? If you’re ready to set up a system to accurate record those inventoriable supplies, calculate the cost of goods made for your creations, and track inventory and COGS totals, then check out our bestselling Inventory for Handmade Sellers spreadsheet. This template will get you ready for tax time.

Wanna learn about this topic in a video format? I cover inventory in-depth in my course, the Get Legit Toolkit, which you can learn all about at the end of this free tax training. In the Get Legit Toolkit, we dive into ALL the in’s and out’s of inventory, and I answer tons of questions about how to deal with tough items like fabric, vinyl, paint, thread, and more. We also discuss the best ways to get caught up on inventory if you’re behind.

Now that we’ve covered inventory, let’s delve into cost of goods sold and what actually goes on your tax return. Click here to read part 2, all about cost of goods sold

All information on this site is provided for general education purposes only and may not reflect changes in federal or state laws. It is not intended to be relied upon as legal, accounting, or tax advice. We strongly encourage you to always consult with a tax or accounting professional about your specific situation before taking any action. Please read our full disclaimer regarding this topic.